Myajlar is one of the last towns on the Jaisalmer border, which, at 464 km, is one of the longest that India shares with Pakistan. The village was one of the key locations for the 1965 Indo-Pak war. Villagers who are old enough remember watching Indian army tanks ploughing through their kachchi roads.

With no more than 2,900 people, Myajlar sits at the edge of the Indian Thar desert border. In summer, the wind blowing across it only contributes to the dry, harsh heat. Temperatures exceed 50° C in the day. “It only rains once every two-three years here,” says Jeetu Singh, who is the de facto sarpanch of the town. Singh’s sister-in-law is the sarpanch but he takes care of most of her responsibilities, he explains.

This is the land of camel tracks and shifting sand dunes, of craggy rock plateaus and salt-encrusted lake beds—an inhospitable environment that is impossible to navigate, let alone live in for all but the hardiest. And that is what the people who live here claim to be.

“Life in border towns is definitely tough, but the people are hard workers. If they could find work, they will go above and beyond to fulfil it. They aren’t scared of hard work at all,” says Kasab Singh Sodha, a 65-year-old retired Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB) officer, who grew up no more than eight kilometres away from the Indo-Pak border in the village of Karda.

Here, in district Jaisalmer, entire villages descend from the one family. “Everyone is related, our great-grandfather or mothers are the same and then the familial line diverges with marriages,” says Sodha. He and his family have lived in Karda—known as India’s last village—for over five or six generations.

Their lives straddled the invisible line drawn in 1947, long before India put up the wire fences in 1971. “Earlier there was no border,” says 80-year-old Ranu Lal. “When it rained, our herds would smell the grass on the other side and run there to feed. We would have to go a hundred kilometres to get them back.”

Lal, along with two other men from Myajlar, worked as guides for the army. However, most people here are dependent on whatever they can earn as herders of cattle and goats. Sometimes, like in the 1965 war—when Pakistan’s troops captured the villages around Myajlar and the town itself—they worked as the army’s supply chain, going to and fro to Indian army encampments with water and rations.

“The government had first said that they will evacuate the village but then the villagers themselves told the government, ‘no, you fight, we are with you and we will fight alongside,’” says Sodha, recalling stories his father told him. During the 1971 war, he was only a year old. “In 1965 and 1971, both wars, our villagers aided the army in the fight,” he points out. “Our people helped a lot—we would take rations and water to the soldiers on camelback.”

Villagers would fill up large saddlebags —“pakhals”—with water and rations for soldiers, load it on to their camels, and supply the army that was then fighting back Pakistani troops at the Jaisalmer border. “Each pakhal can carry about 100 litres of water,” explains Sodha.

Today, sharp wiring through which electric current runs at night, and floodlit poles cordon off India’s land on the boundary—the subcontinental country has fenced 2,064 of its 3,323 kilometres of border shared with Pakistan.

The bottom of Lal’s walking cane is iron-clad and clinks softly when he walks around his three-room home shared by ten people. He served as a scout in both the 1965 and 1971 wars, guiding troops into Pakistani territory, identifying Pakistani encampments ten to fifteen kilometres ahead of the army’s platoons. “It’s dangerous work—that’s why I got recognition,” he says, laughing and pointing towards his medals of valour.

“Daily we see our elderly dying for lack of medical care, our cattle dying for lack of water and fodder…we face death every day that we live here.”

Lal recalls capturing soldiers alive, and also his lost comrades. Though the three scouts from Myajlar came back alive in 1965, they lost six army officers. One of them, Lance Havildar Deb Singh Bhandari, died while stopping an enemy machine gun. The village erected a remembrance monument for the six officers, and the others who followed in skirmishes during the 1971 war as well. But the memory has only made them bolder. “Rajasthan doesn’t feel fear,” says a proud P. Soni, who is assistant to the Jaisalmer district magistrate.

When word came to Lal of fresh tensions flaring up post the April 22 Pahalgam terror attack, he walked into the local Border Security Force (BSF) post, the police station, the army office—everywhere—with a letter: “I am ready to be an army guide again.”

If he must die, he would prefer it to be on the battlefield, honoured, rather than quietly at his home. “At least if I die serving my country, the government will give me salaami.”

A War for Necessities

In the border villages in Jaisalmer district, Rajasthan, death is never far from the minds of the people. “We have stared death in the face,” says Lal. But it is not wars between nations that he is talking about. “Every day we see our elderly dying for lack of medical care, our cattle dying for lack of water and fodder…we face death every day that we live here,” he says.

Lal and others in the border villages fight a different daily battle: for potable water, electricity to run their homes and borewells, and land on which they can grow food for their families.

Myajlar receives an average of six inches of rainfall per year—a fifth of the 30 inches that India gets on average. The region is prone to droughts. “It rains here once every two-three years,” says Singh, glancing up at the clear sky, anger clouding his eyes. In between those times, the villages depend on borewells for water and to irrigate their fields. However, electricity, too, only comes to the area for “about two-three hours a day,” Singh adds. This makes the borewells useless for the other 19 hours. “There is no timing for power cuts,” says Singh. So, whenever the electricity runs—be it in the middle of the night or during the scorching day—the villagers ensure to collect enough to irrigate their fields and to provide water for themselves and their herds of cows, camels, and goats.

During dry months when the heat shimmers across the land, there is no electricity, which means there is no water. Karda’s villagers lose a large number of their herds, their only steady source of income. “When it rains, there’s grass and that’s what the animals eat; when it doesn’t rain then they don’t eat…like right now, many of our herd are dying for lack of water and food. There is no government fodder depot here. I wish they would open one here,” says Singh.

In Karda, until 2019, there was no road to connect the village to Myajlar, the nearest developed town. An unpaved track linked the two. Sodha remembers how he went to school in his youth. “I used to walk five to six hours a day to get to Myajlar from where I would catch the only bus that went to Jaisalmer,” he says. A 35-km journey that both schoolchildren and adults used to make on camelback or on foot “if no one had a spare camel.”

Now that there is a road, other problems have come into focus. Besides electricity, water in the border villages is a scarce resource. There have been improvements over the years. The 500-odd villagers used to depend on two hand-dug wells from which they could harvest nothing but hard, mineral-laden water. “The water was khara, you could not even wash your hair with it. And it was totally unfit for irrigation,” remembers Sodha’s wife Hawa Sodha.

“The problem is that the government’s improvements never get here,” says 55-year-old Kamal Singh who grew up in Karda. “There is an RO plant but it stands empty; a village tank that remains dry,” he adds. Villagers say that most of them don’t have land to irrigate or farm on. “The last time there was land allotment here was 50 years ago,” says Singh, who shares ten bighas of land inherited from his grandfather between his five brothers. Lal, for his part, has inherited a few dozen bighas from his father, but it is scarcely enough to feed his 15 descendants. His five sons and ten grandsons, all educated to high-school level, are jobless. Some of them passed the exams for the security forces and civil service posts but were turned away at the last moment. His son spent 20 days living inside an army station in Bengal, only to be chased out when an officer demanded money. “Whoever pays gets the job,” Lal says.

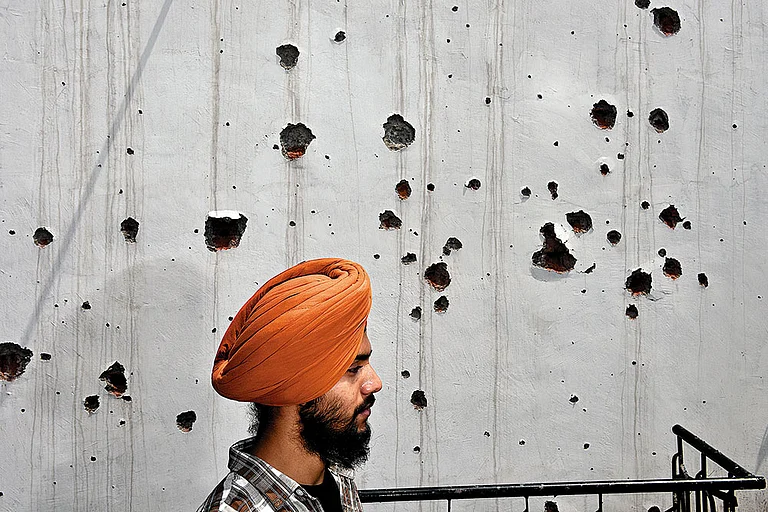

In September 2024, Jeetu Singh’s brother was grazing their cattle herd when he saw a glint of iron in the ground. During the monsoon, rain washes away the thin layer of dirt that covers old minefields—remnants of the 1965 war, when Pakistan’s troops occupied these villages for three months, and Indian forces mined the approaching fields to help drive them out.

That day, Singh’s brother exposed half a dozen anti-personnel mines near their pasture and the jungles around their fields. The villagers all know what these landmines look like because finding these is a regular routine for them. Minefields once spread six to eight kilometres inland, with the Indian army burying over 800,000 devices along Rajasthan’s border.

The villagers have grown up on stories of the landmines and unexploded bombs left from the war killing people. Two goat herders were blown up in the early 80s, having stepped on the wrong spot. One man was burned alive after he found a box-like explosive device and tried to open it, thinking he had found a treasure.

Should anyone get seriously ill or hurt in the border villages, there are no proper local medical facilities. Karda has one nurse in the village of 500, and they only stock basic first aid. “For anything more serious, we go to the hospital in Myajlar,” says Sodha. That hospital is a one-storey building housing only one doctor for the entire district. “At best, the doctor can bandage you and give you a painkiller and send you off to Jaisalmer for treatment,” says Singh.

So, what happens in case of a serious injury or a medical emergency? “You get ready to die, what else?” says Singh.

Lack of jobs and facilities in border towns has had a dual effect—most of the youth are leaving to find a better life elsewhere, and those who stay find themselves forced into bachelorhood. Twenty-three-year-old Viru Singh mans a medical store in Myajlar and lives with his aged parents in the village. He used to live in Jodhpur where he ran a hostel, but as his parents grew older, he gave up that life and came home. Now, he lives in a forced singlehood, he says.

“No one wants to marry their girls into a border village—why would they? Life is hard here,” he says. So, two-thirds of the young men in Myajlar and the neighbouring villages are unmarried and have no hope of finding a partner to share their lives.

Those who could have found a way out. Ranu Singh ensured his daughters married outside of the villages in the city of Jaisalmer. His sons, the ones who are not sitting idle in the village, have left to find work in larger cities. Singh says young people are leaving the villages in droves. There are no jobs, not even in the army or in the BSF, which has a base just a few kilometres from Myajlar and in Tanot, the other border village.

The villagers are not the only residents of the Thar border. Alongside them live officers of the BSF—India’s first line of defence in case of war or invasion. They are also fighting another, very human, battle: one against isolation. “We are in bases next to the border where we don’t see civilians for days at a time—we don’t see anyone for days at a time…it leads to a lot of feelings of isolation,” explains Manisha Meena, a commander at the BSF base in Tanot. Twenty-four year old Meena is one of a handful of women commanders on the base.

Just 500 metres away is the wired, electrified fence that separates India from Pakistan. Commanders like Meena spend over nine hours at a time by this wire—patrolling it on foot, by jeep, and by camel. More often than not, they see nothing but sand. This can lead to fatigue and boredom. “How long can anyone ask a person to stand and stare?” says DIG Y.S. Rathore.

For the upper echelons of the BSF, the real challenge is keeping their praharies (troops) motivated and war-ready. This is achieved through a plethora of methods including instilling national pride in their work, team bonding exercises so the platoon feels like family for the officers, and visits from higher-ups, who emphasise the importance of the BSF’s work.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one BSF officer shares: “To live life as a BSF officer means you will miss your other life completely—you go home for a few months in the year, you never see your children, you don’t get to speak to them about your work so they don’t know really what you do… it is a lonely life and an isolating one at that.”

“We Don’t Run”

Despite the difficulties—the heat, the thirst and hunger, the landmines and corruption—citizens of border towns are proud of the fact that they “don’t run,” says Kamal Singh. This land is theirs, its harshness a test of their character—and they take pride in that. In times of heightened tension—whether missiles, drones, or mere rumours fly around—villagers follow official directives to stay indoors. But as seen in Lal’s case, they long to fight alongside the force, or help in any way they can.

When peace returns, life must go on. In the fierce sun, women in bright ghagra-cholis walk barefoot to draw water; men haul fodder in trucks, hoping to feed their herds. A 1,450-km border road project announced in February 2025 is meant to improve patrolling and anti-smuggling efforts, but locals wonder if it will ever bring them a reliable electricity grid.

Behind the material problems lies a deeper yearning in the heart of these citizens: they want the border to mean more than an invisible line, a wired fence. “The border towns are always willing to fight for India, but when will the government and our netas fight for us?” wonders Singh.

(For full version of this article, go to www.fabric-uk.com)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Avantika Mehta is a senior associate editor based in New Delhi

This article is part of 카지노 Magazine's June 11, 2025 issue, 'Living on the Edge', which explores India’s fragile borderlands and the human cost of conflict. It appeared in print as 'Feild's Of Nowhere.'