When a car flips and topples through the air, or a powerful kick shatters glass—it incites excitement, suspense, fear and adrenaline in the audience. Watching a hero survive explosions, fight hundred men, or leap across buildings taps into the fantasy of invincibility and justice. To viewers, it represents a certain sense of heroism, masculinity or nationalism. Sometimes, it satisfies a deep desire for control in an uncontrollable world—especially when it comes to the common man’s revenge against the system. Some actors prefer doing their own stunts but most of them lend their faces to stuntmen and body doubles, whose labour and expertise brings the illusion to the big screen. Action and entertainment genres go hand-in-hand and are quite inseparable. The writing, blocking, execution and safety protocols that make up one scene are unknown to most—the plight of stuntmen, even more so. So, what does it take to stage a perfect fight sequence or a car stunt? And what are people willing to sacrifice to deliver that experience to us?

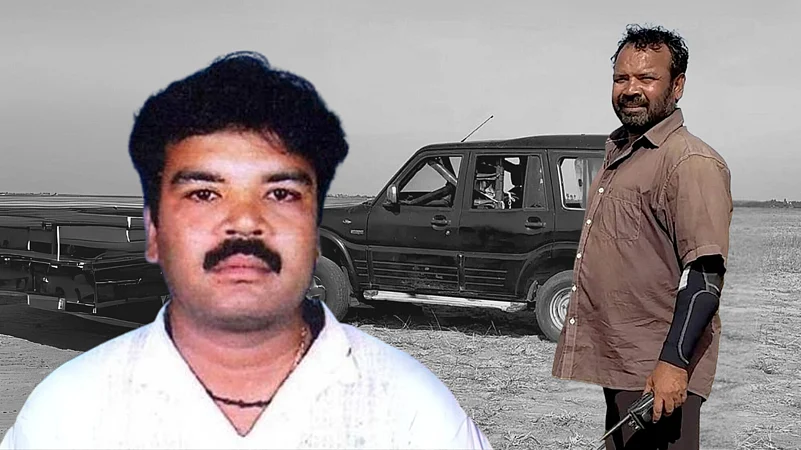

Recently, on the set of Pa Ranjith’s Vettuvam, seasoned stunt professional Mohan Raj (SM Raju) lost his life in a fatal car stunt mishap. In a profession that demands precision, risk, and physical mastery, their names often remain absent from credits, contracts, and conversations—until a headline or report forces the industry to spell it out. These deaths speak less of fate and more of an industry that benefits from their danger, yet refuses to protect or honour them until it’s too late.

Rizwan Kalshyan, based in Mumbai, works as an actor and stunt double in the Hindi film industry. He has worked in several films as Shah Rukh Khan’s stunt double, including Jawan (2023), Pathaan (2023) and Dunki (2023) and stepped in for many other actors as well. Currently, he’s shooting as Ranveer Singh’s stunt double in Dhurandhar (2024). Many enter the stunt industry with limited experience, driven by financial desperation. Years of skill and mastery are often sidelined by the urgent need to earn. Reflecting on what draws people to the industry, Kalshyan says, “A lot of young people get into stunts for the money—I too, was one of them. But the price you pay for inexperience is huge. Nothing can replace experience, and without it, the job becomes even more dangerously unpredictable.” Production houses, too, prefer hiring the young and risk-ready over seasoned professionals. In most professions, experience ensures seniority and better earnings; in stunts, the younger and more disposable the body, the greater the demand. Yet, a stuntman’s career is fleeting; the body inevitably weakens, injuries accumulate, and recovery slows. Without insurance or basic protections, these artists are expected to survive on passion alone.

Industry professionals and action directors uphold strict safety measures, fully aware that even in controlled settings, accidents, though infrequent, can still occur. Risk is inseparable from the nature of stunt work. The argument isn’t that stunts are recklessly executed or absent of safety—it is more that the danger doesn’t end when the camera cuts. What’s harming them isn’t just the physical risk, but the lack of protection beyond the film sets. Does the industry safeguard their lives off-screen or does its concern end where the performance does?

Stuntmen undergo intense physical training, secure permits through their respective unions, and often wait years before landing consistent work. Fight Master Dilhiip M Raaj, a stunt artist since 2017, has performed over 200 stunt sequences and assisted top action masters in Kannada and Telugu films like Bagheera (2024), Aavesham (2024), and Max (2024). As an independent action director, his recent work includes Mahakaala (2024), The Rise of Ashoka (2025), and Lovely (2025), with more projects in development. Raaj explains, “Stuntmen work in accordance with their unions. Unions grant rate cards that determine payments—ranging from as low as ₹2.5k in South Indian circuits to ₹5k–₹6k in Mumbai.” It offers limited protection through post-injury aid or getting financial compensation for their work from production houses. He also sheds light on the unspoken formalities that underline the profession: “Before joining the union, one has to sign off with the understanding that the risks range from minor injuries to even the possibility of death. Agreeing to all terms and conditions is what grants entry into union membership.” But beyond formal protections, survival hinges on word-of-mouth, with referrals acting as currency in a tight-knit, often opaque ecosystem.

Women stunt professionals in India remain largely invisible—almost absent in the South, and scarcely present in Bollywood. Some notable names who have carved a space for themselves are Sanober Pardiwalla and Geeta Tandon. This absence is shaped in part by the lack of women-led narratives, with few such films in Bollywood and even fewer in the South.

Stunts are systematically written, choreographed, rehearsed and then performed. Even then, their careers remain hostage to the body’s resilience. Kalshyan points to the obvious yet often uncomfortable truth at the heart of the craft : “Even minute miscalculations in safety can cost someone their life. It’s a gamble every single day. You might have the whole stunt mapped out in your head but one unchecked slippery surface or a slightly off landing can completely change the outcome. It is important to have experienced action directors who are aware of every situation that can go wrong.” Even with all safety protocols in place—one wrong fall, one misjudged fire cue, and what follows may be irreversible: broken limbs, impaired senses, or damaged motor skills. These injuries are often lifelong, internalised as part of the job’s demand in an industry that renders its artists dispensable. Even actors who claim to perform their own stunts are rarely permitted to risk their lives; stunt doubles step in to assume that danger. Yet, these professionals remain largely uncredited, overshadowed by the prominence of familiar faces. Their essential contribution ranks far below in the hierarchy of recognition, despite the physical demands and consequences their work entails.

The body becomes both the tool and the cost, and when it gives out, so does the livelihood. Raaj highlights the dire consequences faced by many in the stunt industry—sidelined by permanent injuries, left without work and compelled to navigate difficult compromises for their family’s survival. Kalshyan, too, recalls an early instance from his career that stayed with him—“A stuntman once asked me to place a hand on his shoulder, and I was shocked to find no collarbone. Another had lost vision in his right eye after a gun misfired on set. One still carries glass shards in his face from a stunt years ago. Most can’t afford costly surgeries, so they simply carry on.” One accident might make headlines, but it is quickly forgotten. The camera keeps rolling, a new stuntman steps in, and the machine moves on.

An obvious solution that comes up is animating or using VFX for the more dangerous stunt sequences, but this is where realism in action takes its chances—to pull audiences back in, offering big scale and excitement. It is also often the case that directors lean towards realism, favouring its texture and tension over animation. Raaj interjects, “In some bigger-budget films, using miniatures, VFX, or green screens may help cut down human risk—but that also makes us feel that our skills are replaceable and endangers our jobs. Realism costs less to produce and is more preferred in Indian cinema.” But the price of realism is risk—it comes built into the job.

Nevertheless, baseline protections must be non-negotiable: health insurance, financial aid, and legal safeguards should be standard, not optional. Behind the spectacle of high-octane sequences lies a rushed, resource-strapped process that often compromises both safety and craft. Kalshyan reiterates, “Stuntmen are expected to deliver top-quality performances, but rehearsals are sometimes skipped due to shortage in time or budget and it shows in the final output. That drop in quality ends up affecting the stunt director’s reputation, too.” Financially, when attempts are made to insure stuntmen, they often reveal the gap between policy and practice. Coverage exists on paper, but rarely protects in full. Delays, loopholes, and token amounts reduce the gesture to formality, offering little beyond optics. Raaj also mentions, “Recently, within the last few months, life insurance of upto ₹2-3 lakh has been permitted. After a stunt professional retires, a minimal amount can be expected from the union as well.” Through initiatives like Akshay Kumar’s effort to provide insurance coverage for over 650 stunt professionals, they are now eligible for cashless medical treatment of up to ₹5.5 lakh. How are our most beloved stuntmen—who stake limb and life—expected to survive, recover from injuries and provide for their families on such abysmal wages? The question isn’t rhetorical; it is structural, and long overdue.

Stuntmen like Parvez Kazi, Vikram Singh Dahiya, Asif Mehta, Riyaz Shaikh, and many others have been instrumental in crafting some of the most unforgettable moments in Indian cinema. The industry needs to honour that labour with value that is equivalent to the impact they create. Stunt rig man Elumalai lost his life on the sets of Sardar 2 (2024), after sustaining fatal injuries from a fall. During the shoot of Viduthalai Part 1 (2022), stunt master N Suresh died after falling from a height as well. Stuntman Vivek was electrocuted on the sets of the Kannada film Love You Rachu in 2021. Many names never even make it to the news.

Recognition must emerge not from mourning, but from a minimum standard of dignity—through rightful credits, sustained visibility, equitable pay, and dedicated awards. Stunt performers shouldn’t need to lose their lives for their names to matter. If someone has risked their life for a film, they deserve credit—at the very least. It marks presence, acknowledges labour, and counters the routine invisibility of those the industry depends on most. Recognition, in its truest sense, affirms their commitment while they’re still alive to claim it.