In Poonch town, the raining mortars did not appear to care much for religion, age or routine.

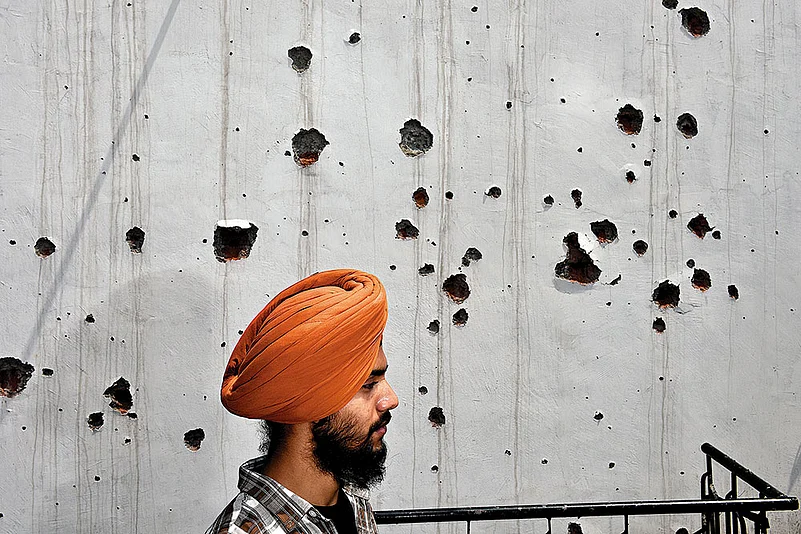

A large green and white wall of a 50-year-old large Islamic seminary, the Jamia Zia-ul-Uloom, still carries the scars where shrapnel tore through recently. In it, on a bed, a 47-year-old teacher lay soaked in blood, before doctors at a local hospital declared him dead. Down the road, a 12-year-old child, drenched in blood, collapsed and died in the arms of a middle-aged man. In another street in the town, a mortar shell rammed through the ceiling of a house; its scraps tearing apart a Sikh man’s turban, leaving his nephew dead.

In Poonch, there’s barely a street where people haven’t either wailed for lost kin or called for help as mortars whistled down on them from the ridgelines along the Line of Control (LoC). The shells “indiscriminately” fell in crowded lanes, past shopfronts or low-roofed homes.

Until 2019, a bus ran across this border, transferring people, goods and shards of culture across either side. Now, it’s time to hunker down in bunkers and count the walls mangled by the mayhem. Elsewhere in Jammu’s border belt, residents crouch in corners, familiar with the drill. Each fresh round of fire revives memories—Pulwama in 2019, the Parliament attack in 2001, the war in 1971…

In Jammu and Kashmir, over 590 villages with a combined population of more than six lakh are located within five kilometres of the Line of Control (LoC) and International Border (IB) in the five districts of Kathua, Samba, Jammu, Poonch and Rajouri in the Jammu division. Of these, around 448 villages remain vulnerable to direct artillery fire from Pakistan.

India has accused Pakistan of repeated ceasefire violations, with small arms fire a routine occurrence along the LoC and IB. Since 2018, incidents of ceasefire violations and cross-border firing in Jammu and Kashmir have steadily increased. From 2018 to 2021, ceasefire violations rose sharply, with 5,601 incidents reported between November 2019 and November 2021; the count increasing with each passing year.

Following the April 22 terror attack in Pahalgam that killed 26 people, border tensions have escalated. Heavy shelling by Pakistani forces hit civilian areas up to 30 km from the LoC, killing at least 17 people in J&K—13 of them in Poonch—and injuring several others. While a fragile calm now prevails, fear still grips border residents. Many say they are unprepared for renewed conflict, citing poor health services, a lack of bunkers, and shortages where shelters exist. Residents say the authorities have also failed to set up proper infrastructure in the main town of Poonch as well as nearby villages, Mandi and Surankote, which were hit by the shelling.

On May 7 in Poonch, a mortar shell ripped through Surjan Singh’s ceiling. Shrapnel injured his nephew, Amarjeet, and struck Surjan’s turban before hitting his sleeping son’s head. Both Surjan and his son narrowly escaped serious harm. Amarjeet was helping his family find a safer space in their crowded street home when the shelling began. Their house has no bunker to shelter them during such attacks. Nearby in the Dharati area of the Balakote sector, people rushed into bunkers as soon as the firing started, recalling the violence of 2015 and 2018 when five civilians were killed in similar shelling.

Surjan rushed Amarjeet to the District Hospital in Poonch amid the bombardment. But he rued the lack of staff and equipment at the hospital, which struggled to handle the flow of injured persons. “The shells hit my nephew all over his body and tore his lungs. Poonch was the worst hit, but the hospital lacks even quarters for doctors. It is not equipped for emergencies,” Surjan said, recalling the screams of Amarjeet’s wife and children after the attack.

Locals said elderly people donated blood for the injured as nearly 70 per cent of Poonch’s population fled. They also expressed frustration at the lack of prior warning. “We were told there would be mock drills. Instead, there was a direct attack. No alert came to prepare us for war,” said Sangram Singh, a local resident.

“Where will people go if firing starts again?” he asked. “There are no safe shelters in Poonch town to protect us from constant shelling. The government must build proper infrastructure so lives are not lost. Shells have hit residential areas kilometres from the LoC,” he said.

Shafiq Hussain Baba, who runs a seed store in the Poonch market—where the air is laced with the aroma of kebabs, biryani and incense—recalled the chaos as people ran for cover during the May 7 shelling. “The only priority for the people was to shift the injured to the hospital and everyone was helping out,” he said. Shafiq added that the shelling had reached further than ever before in places far from the LoC, like the Poonch marketplace.

Life in these border areas of Poonch, Rajouri, Kathua, Samba and Jammu districts, is a daily grind under the shadow of mortar shells and shattered homes. Shelling, this time, has pockmarked terrains that previously, over all these years, had been considered safe from the spillover of cross-border hostilities.

“The situation was not even as bad in the 1965 and 1971 wars as it is now. Shells have landed in areas that had never been impacted by cross-border tensions,” he said.

With the tense standoff between India and Pakistan still unfolding, shopkeepers say normal business has yet to fully resume. It will take several months for life to find its rhythm again.

BR Suri, 81, a local shopkeeper, says Poonch town is tense. Shops close early in the evening and open late in the morning. “People are fearful that the conditions between India and Pakistan may deteriorate further. Many businesses remained shut for weeks together,” he said.

According to BJP MLC Pradeep Sharma, mortar shells hit all over the town, including his house, and residents called him urgently, pleading to be moved to safer places during the shelling.

“As I started receiving calls for help, I went out onto the street and took people to the hospital. It was terrible; some people breathed their last in my hands. I saw a teacher from the local seminary succumb to his injuries, and I tied an oxygen mask on another injured person, but I watched helplessly as people died,” he said.

A few streets from the BJP leader’s house in Poonch, two neighbours lost their lives almost simultaneously. They were struck by shells fired by Pakistani troops from behind a mountain that marks the Line of Control. While authorities carried out damage assessments, residents said the losses were worse than during the 1971 war.

“Zain came running towards me and was shouting, ‘save me, save me,’ and as I rushed with him into a house to take cover in its corridor, within moments, he died in my lap at the gate. It was terrible, and the boy was all soaked in blood”.

Ragi Amrik Singh’s shuttered grocery shop was stained with blood that flowed into the narrow street after it was hit by mortar shells. His neighbour, Ranjeet Singh, lay crumpled nearby, struck by mortar shrapnel. On May 7, Balbir stepped out to smoke and shouting, only to find his brother, Ranjeet, killed by a mortar.

“When I went outside, there was a stream of blood flowing. My brother had gone out to help people escape the shelling, but a shell took his life,” said Balbir.

Authorities assessed the damage in Poonch town. Amrik’s family opened their shuttered grocery and crockery shops to heavy losses. Mortar shells had shattered glass cases, damaged the fridge and wrecked crockery.

According to General Secretary of District Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee Poonch, Harcharan Singh, Poonch was relatively calmer than other areas that lay close to the LoC, but this time the damage was heavier than even the 1971 war. “The situation here has remained tense during the surgical strikes and the 2001 Parliament attack, and people get worried over the talk of war. But this time the damage has been more extensive than the 1971 war between India and Pakistan,” he said.

Shells also struck residential areas in Poonch district, including Mandi, Mendhar and Dharati. In Jammu’s Sukha Khatta area, 40-year-old Mohammad Akram died as a mortar exploded outside his house while he fled with his family. His brother, Mohammad Bashir, said Akram is survived by his wife, four daughters and two sons, who have now lost their means of survival.

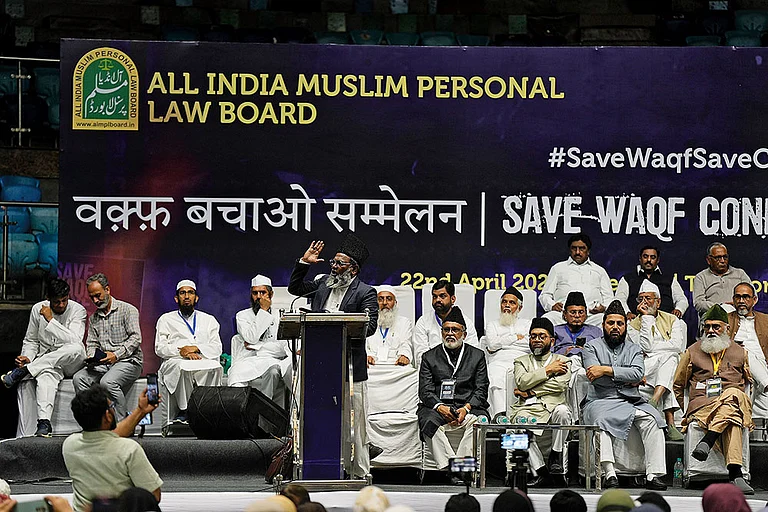

After the shelling at the local seminary, most of the students left for home and did not return to classes even after the May 10 ceasefire. “There were some 500 children who were studying here, but most went home after the shelling here,” said Izhar Ahmad, a teacher at the seminary.

Liyaqat Hussain from Banch said his son was among students who returned home, fearing the India-Pakistan tensions would disrupt their studies again. “My son chose not to return to school immediately, as his safety weighed on our minds,” he said.

All along the LoC and border, especially in Rajouri and Poonch, people fled their homes and performed last rites. In Poonch’s Dungus area, 12-year-old Zain Ali, soaked in blood, ran to Khalid Hussain for help. Moments later, Zain and his twin sister, Zoya Khan, died in the mortar fire, while their father, Rameez Khan, was injured.

“The child (Zain) came running towards me and was shouting, ‘save me, save me,’ and as I rushed with him into a house to take cover in its corridor, within moments, he died in my lap at the gate. It was terrible, and the boy was all soaked in blood,” recalls Hussain. The family had shifted from Mandi to Poonch so the twins could study. The twins, Zain and Zoya, now lay buried alongside each other in their home’s backyard. Their father, Rameez, still recovering from injuries, remained unaware of their deaths. The twins’ father, injured in the shelling, was told days later; he broke down on hearing of their deaths.

After the Pahalgam attack, cross-border firing damaged several homes across Mandi, Mendhar and Dharti. Across the ridge in Bayla village, families huddled in wooden attics as tin roofs burnt hot. On the day Qari Iqbal was injured by shelling, his brother Farooq Ahmad, 42, was at the Seri Khawaja seminary, where he teaches. “We buried my brother a few hours later after he was hit by a shell here at our ancestral village. The funeral prayers were held while the threat of shelling loomed over. My brother had two wives. He has a large family, including a handicapped child, and they have lost a source of support,” Farooq said.

Tariq Manzoor, the deceased’s nephew, said that the lives of the family members have been shattered as they lost their “means of survival”.

Habibullah Khan, a resident of the Mendhar area of Poonch, said that the tensions between India and Pakistan have been giving people sleepless nights. “Several houses have been damaged here due to the shelling from across the LoC. The situation was no different during the time of surgical strikes in areas that lie close to the LoC. We have to bear the brunt of hostilities between the two countries.”

A resident of Dharati, Gulshad Khan, said that the areas close to the LoC, particularly the Balakote sector, have borne the brunt of hostilities between India and Pakistan. “In 2015, five to six civilians were killed in the shelling by Pakistani troops from across the LoC. This time too, there was heavy shelling in residential areas. As soon as the shells started landing here, we rushed to the bunkers along with our family members.” They could feed their cattle only after the shelling stopped.

Gulshad said that although Dharati has several community bunkers as well, where a large number of people can put up, they needed more bunkers. Prior to the shelling, villagers had an arrangement for cooking in the bunkers and also stocked them up with essential commodities. “Bunkers help really to save lives, and we don’t feel the need to move to other places during the border skirmishes,” he added.

However, now, as a fragile calm prevails along the LoC, people are even unable to live in their houses, some of which were heavily damaged. Surjan Singh said he and his son were taking refuge in the neighbourhood’s gurdwara. “The loss is heavy, and the room in which I used to sleep is fully damaged,” he said.

In Dungus, one house bore the brunt of the shelling, with several others partially hit. Muneer Hussain, 40, said shells landed close to many homes. Bits of shrapnel struck his small house, leaving scars on the walls and damage to the shop outside plainly visible.

“None of the government officials have come here to assess the losses. We have suffered damages, and we are fearful that in case the conditions between India and Pakistan further deteriorate, we will have to bear the brunt,” said Muneer.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ishfaq Naseem is senior special correspondent, 카지노. He is based in Srinagar

This article is part of 카지노 Magazine's June 11, 2025 issue, 'Living on the Edge', which explores India’s fragile borderlands and the human cost of conflict. It appeared in print as 'Mortar Memory.'