Soon after missiles stopped flying between Israel and Iran, US President Donald Trump condescended to declare himself satisfied that there was no longer any need for a “regime change” in Tehran. Earlier, he had demanded “total surrender” from Iran’s rulers, failing which the Americans would ensure a change of regime in the Islamic Republic. A huge threat. Magisterial arrogance.

All this glib talk of ‘regime change’ was a throwback to the days of the so-called ‘Arab Spring’. Not long ago, the world was witnessing the barricades being breached in Tunis’ November 7 Square, the siege at Cairo’s Tahrir Square, and the confrontation in Manama’s Pearl Square. We had our own little flutter at Jantar Mantar under Anna Hazare’s nominal leadership.

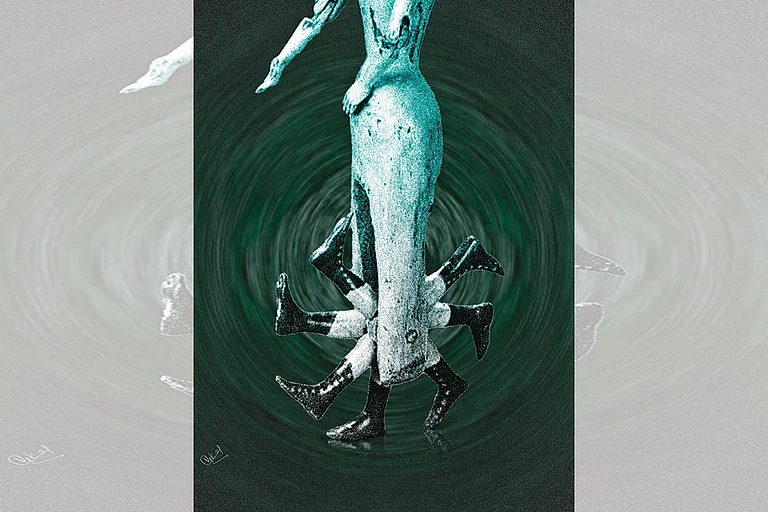

Those were heady days when dissidents were flirting with insurrection; challenging the rule of the old, corrupt, and despotic. The new technology of mass information was being creatively deployed to manufacture solidarities and unity of purpose among the sullen populace. In particular, the “Arab Street” was brimming with hope and defiance. Suddenly, every established state order seemed vulnerable to the dynamics of a “regime change”.

A change of regime, of course, was not a new concept. Imperial powers like Britain were routinely getting rid of uncooperative rulers in the Middle East, without any qualms in using coercion and force to bring about a new set of sultans and amirs in this or that protectorate in the Gulf region.

After the Second World War, the Americans were intervening militarily in country after country, on the pretext of making the world safe for democracy. On its part, the Kremlin was not averse to sending tanks to Budapest and Prague to quell uprisings and to ensure compliance and submission from fellow-comrades in supposedly independent countries. And, after “9/11,” the Americans talked themselves into the indispensability of a regime change in Iraq. That American adventure ended rather badly.

When Barack Obama came to Washington, he brought with him a toolbox of moral imperatives and democratic insistencies. And though the Obama crowd was aware of the mess in Iraq after the Saddam Hussein regime was sent packing, the new president and his principal advisers were in thrall of the American intervention made during Bill Clinton’s presidency in Kosovo; the liberals in Washington had felt good and self-validated in their capacity to put things right.

President Obama was to assert “American interest in democratic governments that protect the rights of their people”. As the self-appointed guardian and policeman of the global order, Obama’s Washington took it upon itself to ensure the rulers—elected or unelected—around the world were nice to their people; in particular, they would not resort to using chemical weapons against the protestors or otherwise engaging in activities that would amount to ‘genocide’. Obama argued: “Some nations may be able to turn a blind eye to atrocities in other countries. The United States of America is different. And, as President, I refused to wait for the images of slaughter and mass graves before taking action.”

Any regime crossing the red lines would come in Washington’s crosshairs, though the accent was to be on non-military options. But if push came to shove, the use of force—as against Muammar al-Gaddafi of Libya—would be the order of the day. Nonetheless, there was an acute realisation that the American voters were in no mood for US troops getting engaged in open-ended entanglements, as in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In the run-up to winning the presidency for the first time in 2016, Trump often mocked Obama’s ‘internationalism’ of the kind that would have, sooner or later, tempted Washington to want to think of ‘regime change’ here and there. Once he won the presidential office, Trump was neither enamoured of wanting to do ‘global good’ nor did he think it was any of his business to ensure that democratic governments did stay true to the spirit of democracy. He had enough enemies at home to tame. The world could look after itself without help or intervention from Washington.

Even in his second presidential innings, Trump remains untroubled by human rights violations or democratic deficits in this country or in that autocracy there. Therefore, it was rather surprising that he should have threatened the ruling dispensation in Tehran with a “regime change” during the recent Israel-Iran war.

At the same time, Trump appears to be intoxicated with America’s military might and its global reach—except, of course, against China and Russia. He seems to be working under the delusion that no country, friend or foe, can stand up to the full spectrum of American power; and, he is fully in grip of his own megalomania to want to order this or that regime to behave. It was this delusion that informed the verbal démarche on Tehran to surrender—or, else...

That threat of a regime change in Tehran was in profound ignorance of Iran and its civilisational resilience. It is fashionable for western observers and policymakers to scoff at the religious clergy (“those Mullahs”) ruling in Iran; but Washington, London, Paris, Berlin and, of course, Moscow have grudgingly sought to work out a modus vivendi with Tehran. The much-derided mullahs have shown staying power; only a madman or a Trump could possibly think of effecting a regime change in Iran.

A regime change, in any case, is a messy and complicated affair. Samantha Power, who was President Obama’s principal human rights adviser, points out in her memoir, The Education of an Idealist, the enormous risks and uncertainties involved in intervening in a country like Libya: “It is hard to know what dormant tendencies lay buried in a society where, for decades, the “Brother Leader” had sought to control even the thoughts of citizens. The Libyan opposition spoke of creating a constitution and an open society, but even if Qaddafi left power, who would maintain order going forward? Since Qaddafi had demolished Libya’s institutions, how would the country function without a strongman at the top?”

Transpose these wise caveats in today’s Iran—and the absurdity of any talk of a regime change becomes all too evident. Citizens of an ancient civilisation would not allow outsiders to meddle in their affair, notwithstanding their dissatisfaction and anger with the “mullahs” dispensation.

In any case, the US has zero moral authority to want to tell the Tehran regime to behave itself or be nice to its own people. Iran is a victim of unprovoked Israeli aggression—an aggression made possible only because of American backing and arms for an extremely cynical prime minister in Jerusalem. Both Israel and the US are guilty of violence and destruction in the region, and it is untenable that Washington could even think of threatening a regime change. On top of this, as president, Trump himself is no practitioner of democratic virtues and values; his critics are already accusing him of destroying America’s institutions and traditions. The pot cannot call the kettle black. Trump’s America stands totally depleted of its moral capital.

Even if Trump’s presidency was not so extensively pockmarked with infirmities and excesses, he would have had no right to intervene in another country’s ruling arrangements. It is for the Iranians or the Russians or the Chinese or the Pakistanis to arrange and rearrange their governing set-up; if they make a hash of it, so be it.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

It is time Washington understood that however altruistic its interventionist impulses may be, it cannot fix a ‘broken’ regime. That is an undertaking for the citizens in each country. This addiction to the idea of ‘regime change’ as a policy tool is a bad habit. Kick it.

(Views expressed are personal)