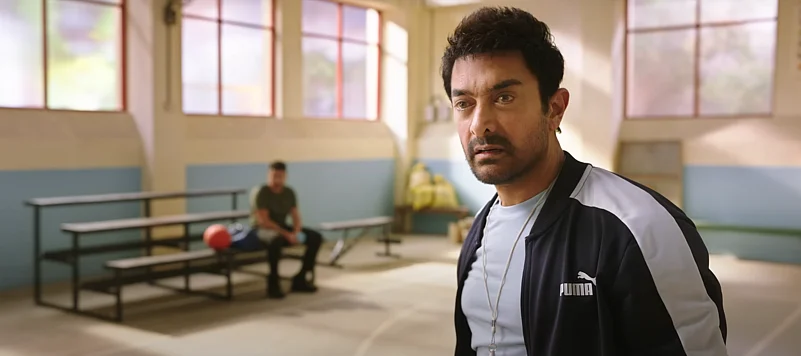

Walking out of R.S Prasanna’s Sitaare Zameen Par (SZP), I was a bit perplexed. On one hand, I was happy that the film was lending a platform to ten neurodivergent actors with central roles, but what also upset me was how the characters remained a “cause” till the very end, for our protagonist, Gulshan Arora (played by Aamir Khan). Khan’s main-character energy has encroached upon quite a few films, starting with SZP’s spiritual prequel, Taare Zameen Par (2008), where he was still relatively grounded, compared to Rajkumar Hirani’s 3 Idiots (2009). It was in Hirani’s adaptation of Chetan Bhagat’s Five Point Someone (2004) that Khan went from being an actor to a savant-like figure—a persona he has maintained for the last decade and a half. In his latest—despite the makers’ overwhelming intent to go in the opposite direction—Gulshan Arora’s flaws feel too manicured and self-congratulatory.

In 2025, the only rule for a film featuring someone who is physically, mentally or socially disabled is to see them beyond their trauma, challenges and/or victimhood—a rule that might be a deal-breaker for an insecure superstar. So committed is the Aamir Khan-starrer to mine its ten characters for pity or laughs that we hardly see them as human beings. In my books, this is a great disservice to the ten debutantes. Do they have nothing else to offer to the film beyond their special needs?

I also couldn’t help but think of Aaron Schimberg’s A Different Man (2024) —a biting satire on showbiz about an actor with neurofibromatosis, a condition that results in tumours growing in different parts of the body. In the film’s case, the protagonist Edward (Sebastian Stan) has tumours on his face, resulting in him only getting auditions for disfigured characters. He never gets a single part because of how he thinks he looks. However, things get all the more hilarious when Edward heals himself through an experimental treatment, and still loses out on the one role he was destined to play—that of a person with his prior medical condition—to another actor Oswald (played by Adam Pearson, who in real life is grappling with neurofibromatosis).

What’s surprising here is how Oswald is defined by his polished, wily personality, in the manner he charms everyone on the set—starting with Edward’s girlfriend and theatre director (Renate Rensive)—and goes on to usurp all of Edward’s friends and his on-set influence. Despite staring us in the face for a large part of the film’s runtime, his condition is hardly an issue compared to Edward’s (with Stan’s perfect Hollywood face) gradually deteriorating mental state, as he’s filled with envy. Adam Pearson is one of the most impressive examples to normalise what many might not term as conventional. One can gauge the seriousness of Schimberg’s commitment towards Pearson, given that it’s their second film together.

If actors with their physical, mental and social disabilities were reduced to just that, we might never have been able to witness a phenomenon called Peter Dinklage. What would Game of Thrones (2011-2019) be without the wisecracks of Tyrion Lannister—or that sensational monologue that Tyrion delivers while facing trial for Joffrey’s death? Closer home, even though Ranbir Kapoor plays a deaf and mute person in Barfi! (2012), he’s never defined by his disabilities. In a bold subversion, Kapoor performs a monologue (in sign language)—something not afforded to Shruti (Ileana D’Cruz), the only verbally proficient character among the film’s three central characters.

There are several examples of substantial roles before Khan to cast differently-abled actors in films, other than as tokenistic inclusions to play saviour to, or catalysts for his character’s transformation. The only way one can be inclusive on screen respectfully, is to see them as well-rounded people, like any other person. Khan might preach sabka apna apna normal (‘normal’ is subjective)—but his gaze towards differently-abled actors in this film is myopic, disingenuous and borderline utilitarian.