The recent Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) circular to offer education in the mother tongue or the dominant language prevalent in the state at the primary level has led to intense debates. This is only to be expected in a multilingual country like India. International organisations like UNESCO have argued that early teaching in the mother tongue will have a positive impact on the child’s cognitive capabilities. Eminent philosopher Paulo Freire argued that the mother tongue plays a crucial role in shaping a critical consciousness, especially among marginalised groups. However, the historical trajectory of every society is unique when it comes to the evolution and usage of languages.

In India, till the colonial encounter, Sanskrit and Persian were the languages of the court, patronised by the elite. Ordinary people inhabited a multiverse which was reflected in their oral and written traditions, be it the Bhakti-Sufi poets or the compositions in the local/regional/community dialects.

The ‘infamous’ Minute of Thomas Macaulay (February 2, 1835)—a pivotal document that significantly reshaped education in British India—added another layer to this language poser. For the British, everything worthy of knowledge was ingrained in their tongue and the rest of the native languages were considered unworthy of attention.

Needless to mention, gradually, a cleavage emerged in society due to the downward filtration theory of the colonial state. The elites quickly imbibed the lingo of the new ruling class and the Indian languages, now called ‘vernaculars’, became the domain of the socially inferior communities. Such ideas did not go unchallenged and Jyotiba Phule dubbed education as the ‘Trutiya Ratna’ or the Third Eye, crucial for the lower castes/classes to attain wisdom and freedom.

Down the line, there have been numerous debates on the medium of instruction in schools/colleges, the official language of the state, and the language in the courts of law. The reality is that the question of language does not exist in a vacuum; it is not value-neutral. Every Indian is aware where he/she is placed in the social hierarchy of the language. There is one language for the market and another to protect ‘cultural values’. For many parents, this becomes a tightrope to navigate, especially if they are multilingual. Even the simple act of choosing the appropriate school is fraught with tensions. To illustrate: if one wants to secure admission in a regional medium school in a metropolis like Delhi, a Kerala School or the Andhra Education Society are options. Such options are limited in cities like, say, Lucknow.

Whose Mother Tongue?

We (the authors) also underwent a similar crisis a decade ago when we were seeking admission for our daughter in Delhi. We speak different mother tongues (Malayalam and Telugu) apart from English, Hindi and Gujarati. Gradually, she picked up all four languages except Gujarati as the other languages were frequently spoken at home. No doubt, there was a period of initial confusion when she was in play school. But by the time she started regular school, she was conversant in four languages, albeit only English and Hindi in both spoken and written forms. The younger the child, the better the cognitive ability to learn new languages and so she is now learning French. She also expresses the wish to read and write in Malayalam and Telugu. At times, she uses Google Translate to convey certain emotions in our mother tongues. So, what is her mother tongue and who decides this? What language can we choose as her mother tongue in official applications?

The discussion around the mother tongue and the dominant regional language will lead to the hegemony of certain languages.

Surely, there would be many families who are multilingual. There are also other cases. For example, the daughter of a migrant family from Bihar, who topped the BA Archaeology and History exam of Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala, studied in a Malayalam medium school. For her family, access to quality education was more favourable than the medium of instruction in their own language.

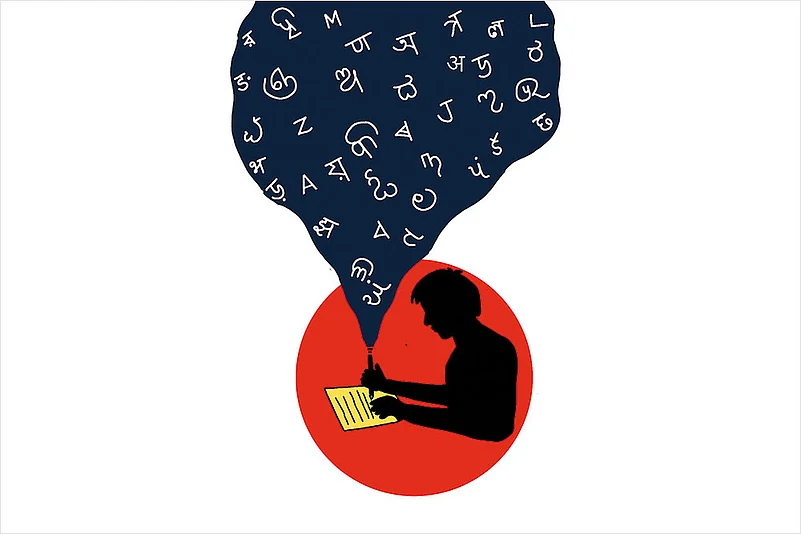

The apprehension is that the discussion around the mother tongue and the dominant regional language will lead to the hegemony of certain languages. In a country where many languages lack a script, exist in an oral form, spoken only by numerically small groups, such guidelines create unnecessary fissures. Though the policy seeks to align with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, there seems an undue haste to implement it. There is no information as to whether the scheme was put into action on a pilot basis, the results discussed and now the operation was being scaled up. The circular was issued in May and by July 2025, schools are supposed to map students’ language choices and make arrangements for teaching in the mother tongue or the local regional language.

In our daughter’s class, students speak different languages—Malayalam, Tamil, Assamese, Manipuri—apart from Hindi. If students are willing, is it possible for the school to facilitate teaching in multiple mother tongues as per the circular? Who will bear the extra burden of appointing/training teachers, designing the curriculum and the new materials? The schools will pass on the additional expenses to the parents. Many institutions in the smaller towns and cities will face more challenges due to the lack of infrastructure and teaching-learning resources.

The Language of Aspirations

Language is used not only to convey emotions; it also reflects the self-worth of an individual as well as ‘merit’. Fluency in English is a signifier of social and economic status, a passport to upward mobility. English is not only a language but denotes all kinds of ‘capital’. Macaulay noted in his Minute that whereas the British had to provide scholarships to children to study Arabic and Sanskrit, people were ready to pay for English education. This is still a social reality, more so for the lower castes/classes. The hypocrisy of the ruling classes is very apparent when their children enjoy the fruits of English education and end up as the Oxbridge elite whereas the ordinary masses struggle for minimum literacy in dilapidated government schools.

The Dalit Goddess of English, envisaged by Chandra Bhan Prasad, as an act of defiance against traditional authority, symbolises these aspirations. In a recent orientation meeting at our daughter’s school regarding the promotion criteria proposed by the CBSE, parents expressed the need for the school to offer foreign languages like French, German and Spanish. They mentioned that students fail to score well in Hindi and it also reduces their employability.

For many schools, the easiest option is to fall back on the dominant regional language, which in North India, is Hindi. Many studies have shown that children in North India are proficient in only one language whereas in the South, they end up speaking multiple languages. In the era of AI and digital literacy, students/parents wish to learn languages which will provide for future employment prospects. The CBSE needs to pay heed to their stakeholders’ aspirations, else such policies will aggravate the already existing systemic inequities in our education field.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

N Sukumar teaches Political Science at Delhi University

Shailaja Menon teaches history at the School of Liberal Studies, Ambedkar University, Delhi