While undergoing gender reassignment surgery, Rudra Chatterji (played by Rituparno Ghosh in Chitrangada)—a celebrated dance choreographer—lies in the hospital bed with the sallow weariness of someone who hasn’t slept in days. Their face is drawn and drained. Their counsellor arrives late at night to visit Rudra and finds them pleading for a stronger dose of sedatives. When the counsellor (Anjan Dutt) hesitates, Rudra reaches for their purse, ready to leave the hospital in search of medicines. The counsellor hastily wrests the purse from their hands, trying to console. Rudra says, “In the middle of the night, when I wake up and see the streetlights, feeling like I should jump from the hospital window—will you come and save me?”

In Memories in March (dir. Sanjoy Nag; screenplay by Rituparno Ghosh), a grieving mother, freshly undone by the private life her dead son never shared with her, visits his apartment. The character of Raima Sen hands her a strip of sleeping pills and says, “My mother sent these for you.” Sleep, in many of Rituparno Ghosh’s films, doesn’t come as respite. It’s withheld, hovering at the edges of consciousness like something half-promised.

I bring it up now because the doctor who declared Ghosh dead in 2013 had reportedly mentioned that Ghosh had long struggled with insomnia and was being medicated for it. It’s not a stretch to say that little happened in Rituparno Ghosh’s films that the director hadn’t already lived through—or at the very least, felt in his bones—as is so often the case with the most honest art.

Battling the Heteronormative Gaze

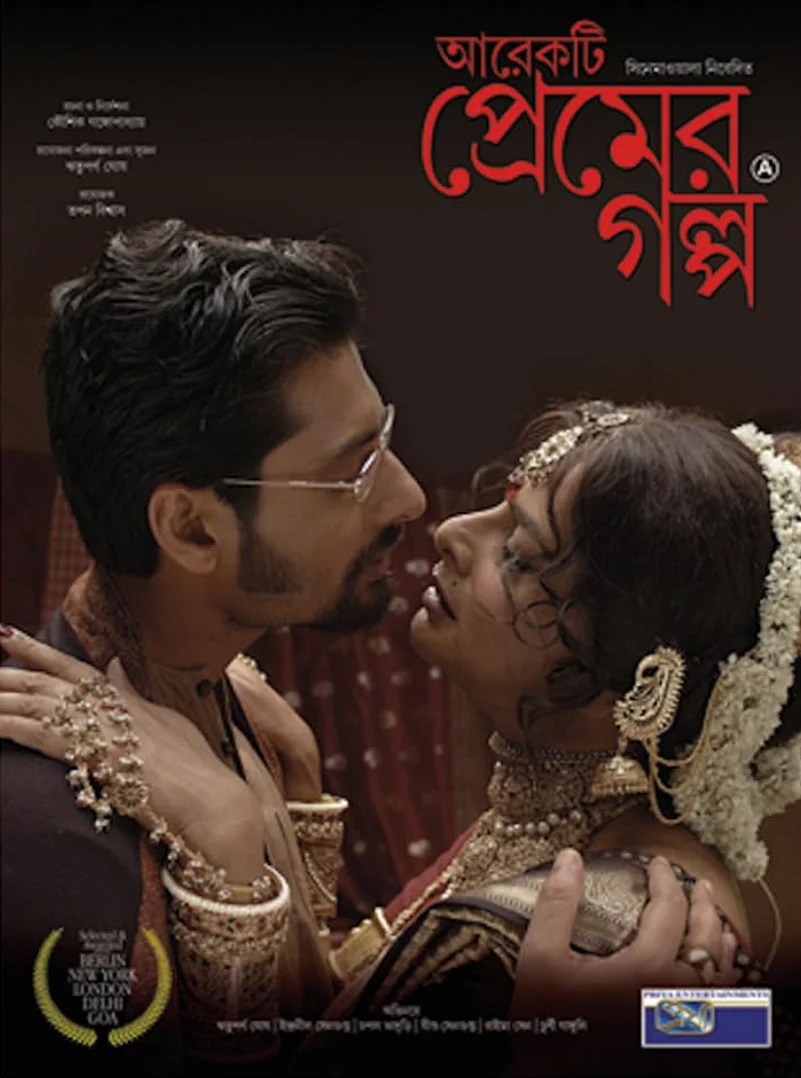

Rituparno’s later films—Arekti Premer Golpo (2010), Chitrangada: The Crowning Wish (2012), and Memories in March (2010)—extend his exploration of queer identity, challenging the heteronormative gaze of the Bengali bhadralok and carving out a space for queer presence in the canon of Bengali cinema.

When Arekti Premer Golpo’s Abhiroop Sen (played by Rituparno Ghosh, who also co-wrote the screenplay for Kaushik Ganguly’s film)—a gender-nonconforming filmmaker—is called a “faggot” by a journalist, or when a crew member points at his femme-coded attire and suggests he change into “plain clothes,” Ghosh’s character retorts, “Am I wearing a uniform or what?”

Similarly, in real life, Ghosh invited RJ, comedian, and TV anchor Mir onto his talk show. Mir—who, at the time, was widely caricaturing Ghosh at award shows and public appearances—was firmly told that if he must imitate someone, he should try to emulate their merit, their talent. To reduce a person to their idiolect and clothing while ignoring their life’s work, Ghosh pointed out, was hypocritical. In Ghosh’s films, as in his life, the politics of bodily autonomy for queer people is not only articulated but defiantly defended—and, more crucially, celebrated.

However, it is the conflict with those closest that aches the longest in Ghosh’s portrayal of queer characters. Dinner tables become fraught with heart-wrenching confrontations and unspoken tension. Generation gap and traditional values firmly take a seat at the table, along with the desire to not conform to predetermined gender roles. Food, much like sleep, is burdened with the weight of the incommunicable and the unacceptable. In the intimate space of a meal with parents or loved ones, nourishment becomes laced with soul-crushing devastation.

In Chitrangada: The Crowning Wish, Rudra sits at the dinner table, trying to invite their father to their production of Tagore’s dance drama Chitrangada, knowing full well he won’t show up. “I have stopped missing you,” they tell him. Their parents attempt to convince Rudra that their loneliness is being manipulated and taken advantage of by their lover. Rudra retorts, “What is better? Being lonely all your life, or finding a companion—even for a while?”

But the characters Ghosh wrote and played—regardless of the outcome—not only entered these confrontations willingly; they directly challenged the heteronormative, homophobic gaze that sought to cage their identity. Rudra Chatterji (Chitrangada), while undergoing gender reconstruction surgery, politely requests the nurse not to call them “Sir,” whereas Abhiroop Sen (Arekti Premer Golpo) mocks his production assistant for calling him “Madam.” These characters, like Ghosh himself, operated from a position of cultural and economic privilege—but they used that privilege to insist on being addressed and treated on their own terms. Not for approval, but to set a precedent.

Desire, Longing and Betrayal

Ghosh’s portrayal of queer love is loaded with unrequited longing and saturated grief. In Chitrangada: The Crowning Wish, he weaves together multiple inheritances—Tagore’s lyrical drama, cultural mythology, and the lineage of queer icons who have desired to live outside the sanctioned frame. In doing so, Ghosh visibilises this lineage and insists on the presence of a queer canon within the literary and cinematic archive.

Tagore’s Chitrangada is born a woman but raised as a man by the king of Manipur, who had longed for a son. When she falls in love with Arjun, she wishes to become traditionally feminine—from kurupa to shurupa. Madan, the god of love, grants her wish. But her transformation unsettles her. Eventually, she refuses the borrowed beauty, while reclaiming her identity as both warrior and woman, defying the conditions placed upon love. Rudra’s story arc runs parallel to Chitrangada’s, where Rudra wants to have children with their partner, and the only way to achieve that is to undergo a series of gender reassignment surgeries. Halfway through that process, their partner Partho (Jisshu Sengupta) retorts that if he has to be with a woman, he would rather be with a “real” one, as opposed to Rudra’s “synthetic” womanhood—and he follows through on that logic.

In Arekti Premer Golpo, Abhiroop Sen is in a relationship with his cinematographer, Basu (Indraneil Sengupta), who happens to be married. When Rani (Churni Ganguly), Basu’s wife, becomes pregnant, Abhiroop’s grief gets captured in a phone call with his mother. He struggles to find grace—even in grief. In both Arekti Premer Golpo and Chitrangada: The Crowning Wish, the birth of a child—or even the possibility of one—becomes a central turning point in the emotional arc of the characters.

These narrative moments gesture toward a deeper and more enduring absence: the systemic exclusion of queer people from the right to parenthood. In India, same-sex couples are still denied the legal right to marry or jointly adopt children. The child, thus, becomes not just a symbol of love or continuity, but of inaccessibility—what queer desire is still forbidden to imagine, let alone claim.

In a cultural landscape that had long relegated non-normative desire to the margins, Rituparno Ghosh’s cinema stepped into the frame and radiantly refused the erasure of queer lives. He practiced what he knew—what he was living through. Whether through a line of dialogue, a sigh across a dinner table, a character glumly removing makeup, or another holding on to a belated lover’s belongings, Ghosh carved out space for the “impermissible.” We, as viewers, learn not only to love the unloved, but also to understand the love of the unloved. His characters do not ask to be accepted. They insist on being seen—as they are. And in doing so, they expose the violence of silence, the frangible nature of social respectability, and the quiet heroism of simply existing outside the badly written script society hands out en masse. Ghosh did not bother offering tidy solutions to the complicated human mind. What he embodied—and envisioned—was the right to be unresolved, and to still be worthy of love.

[Disclosure: Following the practice of many literary scholars, we use he/him pronouns for Rituparno Ghosh, as he preferred to be called “Ritu da.” For Rudra Chatterji, we use they/them pronouns. For Ornub Mitra and Abhiroop Sen, we use he/him pronouns.]

Sritama Bhattacharyya has an M.Phil in Women’s Studies from Jadavpur University, Kolkata. She is currently an English Teacher based in Washington