Words fail to capture *Reema Devi’s plight. This middle-aged woman from Bihar’s Kajra village is distraught and terrified.

Two Families, One Curse: Whispers Of Witchcraft Upend Lives In Bihar

Hundreds of women in rural Bihar have been branded witches and killed by their families, friends or neighbours.

Just about a week ago, one of her neighbours branded her a witch. Half-a-dozen men and women then came to her doorstep and attacked her front door at night. Their weapons left a deep gash in it. Desperate and fearing for her life, she phoned two locals—a ration dealer and his son—but neither helped. With the attackers growing ferocious, she dialled 112, the police helpline. Men from the local Mirganj thana in Purnea district arrived. That’s when everything turned murky.

Reema wants her attackers arrested—but the police and the mukhiya suggest both sides should settle their “animosity”. This isn’t an exception: in many parts of rural India, disputes are expected to be resolved within communities. Taking a matter to the thana can be seen as undermining the village’s authority and order—especially if a woman does it. Because of this, Reema has lost not just her neighbours’ affection, but also their sympathy.

On the street corner leading to her house, a group of men have gathered. An elderly man proclaims, “Dayan hoti hai! Dayan hoti hai!” (There are witches, they exist). He believes he has suffered from their spells. His bones hurt, his body aches—not due to old age, he insists, but due to a dayan. A younger man explains how a leaf, crushed and powdered, can kill a man. A third one speaks of how a dayan can break a man into seven pieces, then stitch him back together. Women stand nearby, listening intently.

The police acknowledge the situation is serious, especially after a family in Tetgama village, which is just over an hour’s drive, was killed on the night of July 6 over a dayan accusation. In that brutal attack, which shocked the entire nation, the victims filed no police complaint. No one dialled 112. A settlement of over 100 families—almost all Oraon tribals—stayed silent as a mob attacked, burnt alive and buried five people. The 16-year-old boy whose grandmother, mother, father, brother and sister-in-were killed alerted the police ten hours later. He accuses a dozen people in the First Information Report, and the police have arrested four. The boy is in the state’s custody, at a location far away from the village.

Reema has heard of that case.

In Kajra, belief in witchcraft is not dismissed. As a pan-shop owner remarked, “Where there’s an ojha, there’s a dayan—the witch doctor who cures and the witch who kills always come in pairs.” According to him, a dayan looks like anyone else—“saamanya, normal”—but a trained ojha can detect who she really is.

That is exactly what Reema is now offering: to have herself “tested” for witchcraft. She is willing to visit any ojha, even in Jharkhand, the neighbouring state where witchcraft killings are more common. “They can burn me, cut me, check me. May I die if I am a witch!” she says.

When urged to stop offering to undergo humiliating tests and witch-doctor assessments, she sounds angry and puzzled. “Well, how do you think I feel, living with that accusation hanging over me?” she asks.

The fear that haunts her is not from strangers, but from her own Backward Sah community. Kajra’s air is thick with fear and superstition, stoked by rumour-mongering from men who pass the time chewing khaini during stints of unemployment.

Why was Reema accused in the first place? Her son Manish, a graduate who coaches children, cradles his toddler as he speaks: “They labelled her so that they are not held accountable when they harm her. The accusation is just a ploy.”

That’s what Reema believes, too.

Another son enters the room mid-conversation. Dressed in a snappy white T-shirt and sneakers, he’s a wholesale merchant in Purnea city. The family is educated and relatively successful. Yet their house is newly fortified with iron bars over the windows for protection from witch-hunters.

The alleged attackers are nowhere to be seen. Their house stands almost deserted, except for a few children and a grown boy who bolts at the sight of reporters.

But Reema does not want to leave Kajra. “Where would I go, leaving my home?” she asks, teary-eyed. Though the community may wish to erase her, she stays on, holding her ground inside her fortified home.

The survivors of the attack in Tetgama knew for 10 days that their family members were being labelled witches. They stayed silent, trusting a community hearing that never happened—or excluded them.

The police call her regularly and have sent across guards. Reema worries what will happen when they leave. When 카지노 approached the Mirganj police station to locate the woman accused of witchcraft, a police companion was sent along, allegedly to assist with directions. “Even we get lost getting there—it’s remote,” said police officer Raushan Kumar. But the escort may be as much about surveillance and protection as guidance. The authorities appear keen to keep tabs on Reema’s safety and the village’s sentiment, and reluctant to confront superstition directly.

The police and the mukhiya fear that arresting Reema’s accusers may escalate hostilities. The community could become polarised, with fresh attacks on her as a response to state intervention. “We’re really trying to keep everyone calm here,” says Kumar.

Naval Kishore Yadav, the mukhiya, is confident. “There’s not going to be any escalation. The moment I get there, I will solve this problem. Nobody will hurt anybody,” he says.

Still, Reema’s ordeal continues. Outside her house, men and women gather. They complain that their hands are tied. “She called the police, so it’s their matter now. We can do nothing! Had she wanted the community’s help, she should not have called the police.” But the two locals Reema had called never helped.

Since then, threats have continued. Reema has been warned of what allegedly happened to a woman in Milki—“An ojha chopped off her legs. That will be your fate, too,” they tell her. The police, however, clarify that no ojha was involved in the Milki case; the incident was a domestic fight.

Children peer over the boundary wall into Reema’s home. People openly watch events unfold. The central question remains: Will the people of Kajra support Reema—the obvious victim—or side with those who attacked her?

The belief in witchcraft runs deep in rural Bihar. Hundreds of women have been branded witches and killed by their families, friends or neighbours. 카지노 사이트 reports quote families of victims claiming that the attacks were “sudden”. But there are always warning signs—such as the accusations and threats Reema faces—that are ignored.

In Reema’s case, there was no illness, no death—none of the usual ruses that precede witchcraft allegations. Only a property dispute between her and her accuser, both she and the police confirm.

“There’s belief in witches due to illiteracy,” says Yadav, adding, “There are no dayans.”

***

The survivors of the attack in Tetgama tell 카지노 that they knew for ten days that their family members were being labelled witches. They stayed silent, trusting a community hearing that never happened—or excluded them. One of the accused is the village Adivasi chief, Nakul, who allegedly led the mob and paid Rs 40,000 to a tractor driver (also arrested) to cart away the dead.

Still, Mirganj Police argue that people in Kajra expect immediate arrests, but “that’s not how the law works”.

How does it work? In Tetgama, while the 카지노 team was interviewing Jagdish Oraon, the brother of Babulal, one of the deceased, district officials suddenly arrived. An official, Rupa Kumari, questioned the deceased man’s brothers: “You didn’t call the police or authorities before or after the attack. How would help reach you?”

Jagdish, the oldest brother, is tired of that question. “I made one mistake—not calling the police, but I was terrorised. People say I must not give witness now. I want justice, but I’m worn out by visiting the thana while the killer mob walks free!”

However the law works, it doesn’t seem to understand that “the community” doesn’t need to be proved right every time—the women it accuses, falsely, cruelly, matter more. But in places like Tetgama and Kajra, the law and the state abandon the people, treating them as backward or irrational.

At Mofussil thana, 4 km from Tetgama, policemen speaking anonymously say, “When tribals beat the drum, Adivasis gather from all over...Adivasis don’t come to the police—they resolve things among themselves.” They add, “The country may have Chandrayaan, but these people have been left behind.”

The policemen express anguish at the killing of innocents, but consider the Oraon not open to “interference”. They also cannot understand why the state government suspended Uttam Kumar, the inspector at Mofussil thana, when the incident occurred: “The government says the police didn’t reach out to the Adivasis enough, and so they lacked the trust to come to us,” says one officer, looking hurt.

In the span of ten hours, a mob of 150 beat, burned and carted away five bodies—unseen by the police.

Today, Tetgama stands divided. Dogs roam the streets, guarding vacant homes. People have fled, leaving behind cows and goats and washing on the line—uncaring of the burn site where they apparently conducted rituals using the victims’ clothes and utensils. The animal husbandry department has sent officials over to tend to their cattle. The people are angry the police got involved—”it shamed our village”, they complain.

Several police personnel guard Tetgama. The Panch, Sunil Kumar, is distraught. But the remaining women say they’re being falsely accused. Sleeping with the fans on, they never heard the angry mob conduct gruesome rites 50 metres away.

And witch-hunting persists. The NGO Nirantar, which surveyed ten Bihar districts in 2024, found that 76 per cent of accused women were 46 or older—beyond childbearing age—and 82 per cent belonged to a Scheduled Tribe. Ninety-seven per cent were tribal, Backward or Dalit.

All the data on hand suggests Reema is at risk. Will she be saved?

It depends on who’s calling the piper. In Tetgama, it isn’t the tribal family. And in Kajra, it isn’t Reema.

*(A name has been changed for privacy)

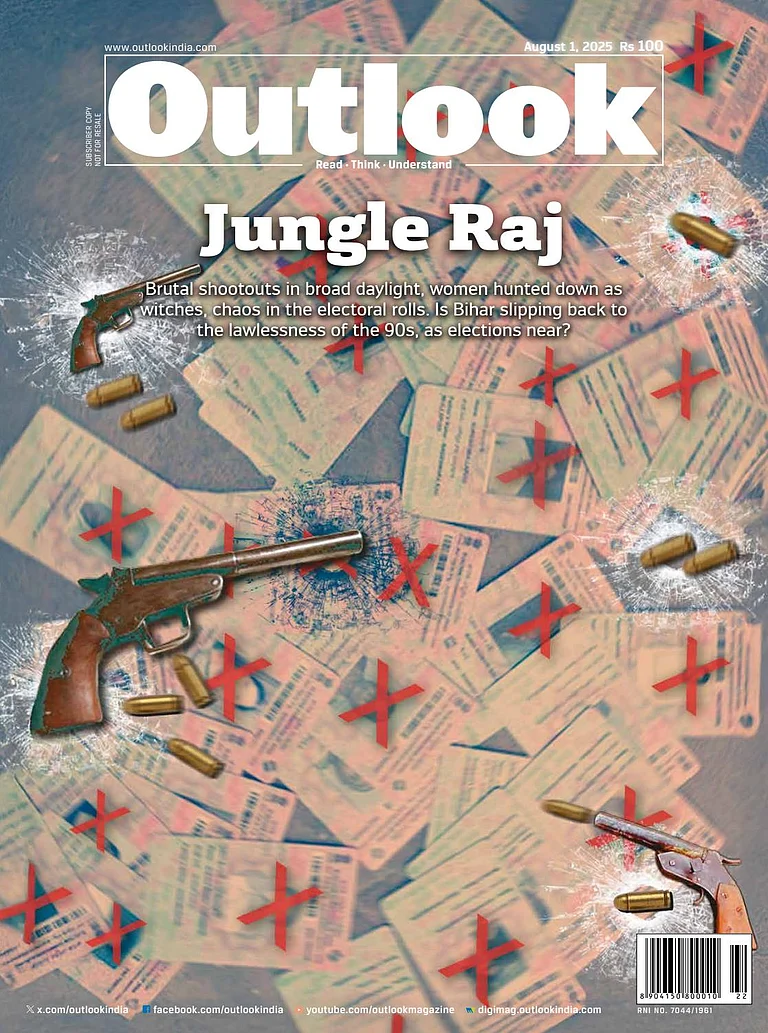

In Jungle Raj, 카지노’s August 1 issue, we explored why the Bihar elections matter so much. Our reporters delved into the state’s caste equations, governance records, electoral controversies and national ambitions, along with taking a hard look at the law and order situation— all of which make the 2025 Bihar Assembly elections one of the most consequential state polls of this electoral cycle. This article appeared as 'The Haunted'.

Pragya Singh is senior assistant editor, 카지노. She is based in Delhi

Tags