She wanted to be political. She came to the United States to study. She believed the two—politics and higher education—couldn’t be separated at a world-famous liberal institution. She’s in her mid-twenties, Indian, and studying at Columbia—a university now more often in the news for crackdowns on student protests than academic developments.

We’ll call her K, though she could be any of the ten students and professors who spoke—off the record—for this story on Indians studying in the US and UK. All carried the same dread: What if the door closes before we finish what we came here for?

Among the Indian students interviewed, the response to changing US immigration policies has been consistent: worry, even fear—particularly at elite East Coast universities. Most of all, international students fear losing their visa status simply for being seen as connected to the protests that erupted after the Israel-Palestine war began on October 7, 2023—whether as participants, organisers, or even observers. They also fear that stating their position on gender and other issues considered “touchy” by the Donald Trump administration could become a tool of ideological enforcement against them.

Ranjini Srinivasan is one such student. Branded “pro-Hamas” in the media, she was forced to leave the US months before completing her PhD at Columbia. Officially, she “self-deported.” In reality, authorities swooped in and gave her no choice but to leave. Columbia quietly removed her from its rolls. India, too, remained mostly silent as students like her were forced out. The silence only deepened the sense of isolation among those facing the sharp edge of the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration.

For K, seeing Ranjini and, later, Mahmoud Khalil made to leave or detained (he was recently released) felt personal. If they could be targeted, so could she—or anyone like her. She had always been politically active on campus. Once, she’d believed activism was integral to liberal education. Now, she’s no longer sure. In the stressful weeks when deportation followed deportation, she deleted her social media accounts—spooked by US government statements about heightened scrutiny of foreign students online. That scrutiny has now been declared official policy.

All through spring, international students whispered about plainclothes ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) officers roaming the Columbia campus. Some, like K, had to show up to classes, but worried they might be identified by dress or skin colour—and detained or deported.

Friends quietly warned students about unfamiliar faces on campus. But no one could confirm if ICE was really present—and that uncertainty fed the anxiety.

“Would I return to Columbia if I knew this could unfold? No. It just isn’t worth it,” K says over the phone. Like many other international students, she’s gone silent online, hoping to erase any target on her back. She’s told her family in India only the bare minimum. Their worry could outweigh her desire to finish what she started: the degree she’s worked years for, and still wants, despite it all.

Stories like this have made headlines in India and beyond, rattling prospective students. One of them, Ritesh, a twenty-something from Delhi, recently chose a university in the Czech Republic over options in the US and UK.

“I got accepted in a few places, but a mix of affordability, the course, job prospects—and of course, the changing mood in the US—tipped the scales for Europe,” he says. Some of his friends educated in India and seeking jobs in developed Western countries are on the verge of giving up. He blames rising anti-immigration sentiment.

“It’s too competitive in the US, and I get the sense they are veering towards preferring locals. Even if we (international students) deserve it, we could still be sidelined,” he says.

The political logic at US universities, many believe, is that elite East Coast institutions—long bastions of Democratic support—have become symbolic enemies for Trump to rally his base against. The result: fear and anxiety among the most vulnerable, the international students. While the situation has calmed since March—after legal pushback against the deportations—the cycle of fear persists. The administration, for example, is re-negotiating the tax-exempt status of several universities.

“Day-to-day life in the US hasn’t changed much. University towns are still mostly liberal,” says an Indian PhD student at UC Berkeley. “But there’s more self-censorship, especially in the Ivy Leagues, and that ripple will hit elite universities everywhere.”

He says he regularly receives worried messages from students back home. His advice? Consider your course and region before writing off the US. “It’s up in the air right now—but European universities aren’t positioned to offer what the US does, especially with funding cuts there too.”

Maya R Jasanoff, a professor of history at Harvard, says the discussion shouldn’t be limited to “elite” universities. “The White House is targeting Harvard partly to send a message to all colleges and universities. (Witness how the government’s efforts to restrict international enrollment at Harvard was followed by reporting that the State Department would scrutinise all student visa applicants’ social media.) Does that mean the US can no longer be seen as the warmly welcoming place for international students it has been for generations? Yes, as long as this administration is in power. I am astonished that a presidency committed to ‘making America great again’ would do something so self-destructive to the US economy and global position,” she says.

Professor Jasanoff is a member of the Harvard chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), which has joined the national AAUP in a lawsuit against the administration, challenging its recent actions and demands of the university as unconstitutional.

All the students interviewed made one thing clear: the policies of the Trump administration don’t always reflect the attitudes of the American public. What shocked K most was that her department—once vocal, even central to anti-war protests—was placed under receivership and got an alarmingly tough “to-do” list from the government. That the student union had to fight for a hotline for international students fearing targeted deportation. That Columbia was blamed for allegedly failing to protect Jewish students during the protests—and that it risks losing millions in federal funding. Meanwhile, few beyond New York seemed aware it was happening.

Then, on June 24, another blow: students at Columbia were told their data had been compromised in a (possibly politically motivated) hacking attack. They were locked out of email accounts and other databases. Images of smiling Donald Trump appeared on campus monitors.

“I used to think they are Ivy Leagues as they have all this money,” K says. “But if they won’t use it to protect students, it’ll amount to nothing.”

According to Paromita Pain, who teaches at the Reynolds School of Journalism at the University of Nevada, some students—especially from the Global South or Muslim-majority countries—are choosing Canada, Europe or emerging Asian institutions as a result of growing mistrust. “Students report feeling that elite campuses are more ideological battlegrounds than spaces for genuine academic exploration,” she says in an email response.

Professor Pain says free speech protections in the US remain strong, “especially on paper”, but certain types of expression—especially related to foreign conflicts (like the Israel-Palestine issue), race, gender, and critiques of US foreign policy—are increasingly subject to social, academic and institutional pushback. “There’s a sense that while these institutions claim to promote critical thinking, they often enforce unspoken ideological conformity,” she says.

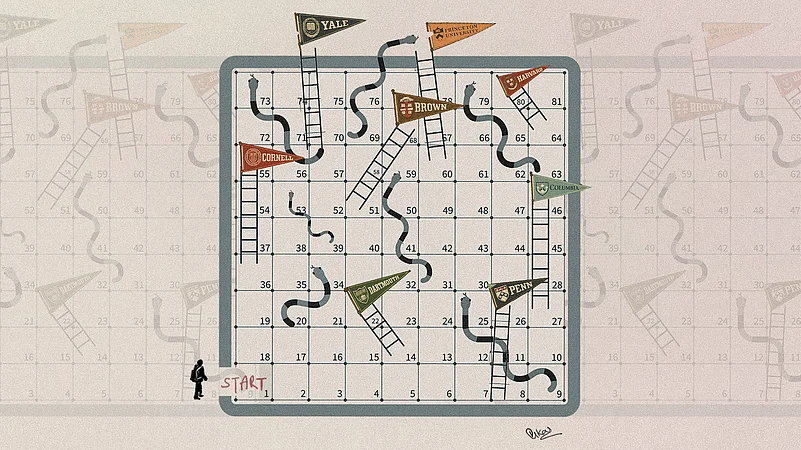

For Indian students abroad, the promise of world-class education is now mixed up with a growing risk perception. The degrees are within reach, but there are cracks on the road there which they might sink into.

(Student’s names have been withheld on request)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Pragya Singh is senior assistant editor, 카지노. She is based in Delhi