Some novels try to tell a story. Others try to build a city. Great Eastern Hotel, Ruchir Joshi’s second novel and most ambitious work to date, is unapologetically the latter—a 900-page fugue on memory, ruin, revolution, and the unending labour of understanding a metropolis that resists coherence. What Joshi attempts here is not just a story of Kolkata, but a reconstruction of its soul. As readers, we do not walk through this novel so much as haunt it—room by room, riot by riot, brushstroke by breadcrumb.

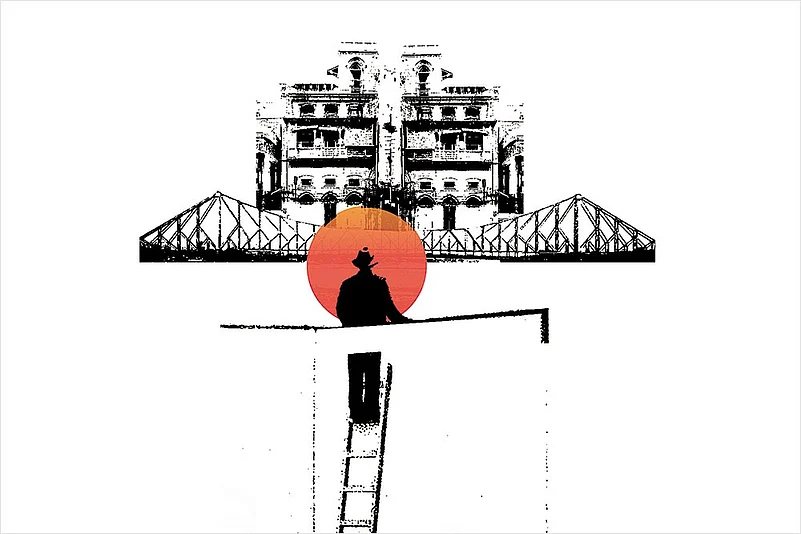

If Sacred Games was Bombay’s maximalist mirror and The Shadow Lines the map of Kolkata’s memory, then Great Eastern Hotel is Kolkata’s mosaic. It’s a book where chronology buckles under the weight of history and art, where the dead refuse to stay silent, and where the eponymous hotel—the former ‘Jewel of the East’—stands as both edifice and echo, repository and riddle.

At the heart of this grandly discursive novel is Saki, also known as Robi Nagasaki Jones-Majumdar, an architectural scholar and reluctant narrator tasked with cataloging the works—and life—of a man he can neither wholly admire nor fully escape: Kedar Nath Lahiri. Kedar is the novel’s haunted keystone. A rakish zamindar’s son turned painter, Kedar is colonial modernity incarnate-a multilingual, sensual, politically indifferent yet culturally voracious urbane man. A lover of women, music, and drink, he floats above the political tremors of his age like a flaneur with a sketchbook. His paintings—described but not exalted—are less masterpieces than symptoms. In fact, the most profound act of artistry Kedar commits may be his destruction of them. Kedar, Joshi insists, is not the artist; the city is.

Saki’s challenge is to trace this man across time—through funerals, famines, uprisings, and intimate betrayals—and to make sense of him. But Joshi, with postmodern glee, undercuts every attempt at narrative order. Saki is not an omniscient guide; he’s a curator of gaps.

Kolkata in the 1940s is a city of war blackouts, Japanese pamphlets, famine refugees, and whispering corridors of betrayal. Through it walk Joshi’s vivid ensemble, which includes Nirupama Majumdar, the steely, passionate Marxist who navigates underground politics and personal loss with equal fervour. She is Saki’s anchor to a more committed generation—and perhaps the novel’s most morally complex figure. Then there is Imogene, a British woman unmoored from empire, watching the collapse of colonial certainties from the vantage of teacups and tectonic shifts; Jerome Lambert, the bumbling British intelligence officer undone not by bombs but by jhaalmuri, a spiced street snack turned metaphor for the subcontinent’s quiet insurgencies; Gopal, aka Gogai, a street-smart orphan whose Dickensian trajectory—from petty theft to black-market broker—embodies the novel’s preoccupation with moral ambiguity and social mobility in a city that chews up and occasionally elevates its most invisible children.

Each of these lives intersects—sometimes directly, sometimes obliquely—at the Great Eastern Hotel, a place where revolutions are whispered, affairs are kindled, and fates are sealed. The hotel is not merely setting; it is character, memory, city. It is, as Saki muses, “an origami of time”.

Joshi, who is also a filmmaker, does not tell the story straight. Time folds, collapses, and spools out like reels of forgotten footage. Rabindranath Tagore’s death opens the novel in a moment of civic grief so vividly rendered it bleeds onto the page. From there we move to the Bengal famine, the Quit India movement, the Tebhaga peasant revolts, and on to the Naxalite insurrections of the ‘70s. Joshi’s lens is sweeping and granular: an aerial shot of the Victoria Memorial being covered in cow dung to protect it from Japanese air raids gives way to a close-up of two starving women speaking Bangla laced with the accent of Comilla.

In the hands of a lesser writer, this would be cacophony. In Joshi’s hands, it becomes a symphony of absences and presences. His characters do not move through history; they are moved by it—tossed, silenced, awakened.

There is a tension at the heart of this novel between the act of representation and the impossibility of capturing the truth. Kedar’s paintings, though central, are deliberately underwhelming—mimetic, imitative, never quite transcendent. Nirupama’s idealism frays. Saki, for all his archival efforts, is left with shards. Even the hotel, eventually refurbished and sterilised, loses its ghostliness. This is not a bug—it is the point. Joshi isn’t writing about heroism or resolution. He is writing about the limits of narrative itself. As one character says, “Every storyteller, especially of history, must confront the gap between accuracy and truth.”

If there is a heroine in Great Eastern Hotel, it is the city itself: sultry, septic, stubbornly alive. Joshi writes Kolkata with a journalist’s detail and a poet’s license. He captures not just its smells and skylines, but its arguments—between languages, between classes, between political urgencies. The book’s humour—often sly, always local—grounds the epic scale in the ordinary absurdity of life.

This novel is not for those seeking tidy arcs or fully animated characters. It is for readers who believe, as Joshi does, that a city is best understood not in a single story but in a tessellation—of gossip, blood, rainfall, revolution, music, art, hunger, and improbable grace.

In the final pages, Saki hasn’t finished. He is on a break. The stories remain incomplete. But perhaps that, too, is the novel’s deepest truth: that Kolkata, like memory, like art, is never finished—only interrupted.

With Great Eastern Hotel, Ruchir Joshi has written not the Great Indian Novel, but something stranger and more necessary: a flawed, luminous, maximalist love letter to the city’s layered soul, written in the margins of a dying empire and a fraying republic.

The hotel may be renovated. The rooms may change. But the ghosts remain. And we, lucky readers, are permitted to walk among them.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ruchira Gupta is an Emmy-winning documentarian, NYU professor & author of The Freedom Seeker & I Kick and I fly